Making Sense of the 2024 Presidential Election Through Dave Chappelle's Racial Draft

How a comedy sketch can show our fraught and shifting race/ ethnic categorizations that manifested with the re-election of Trump.

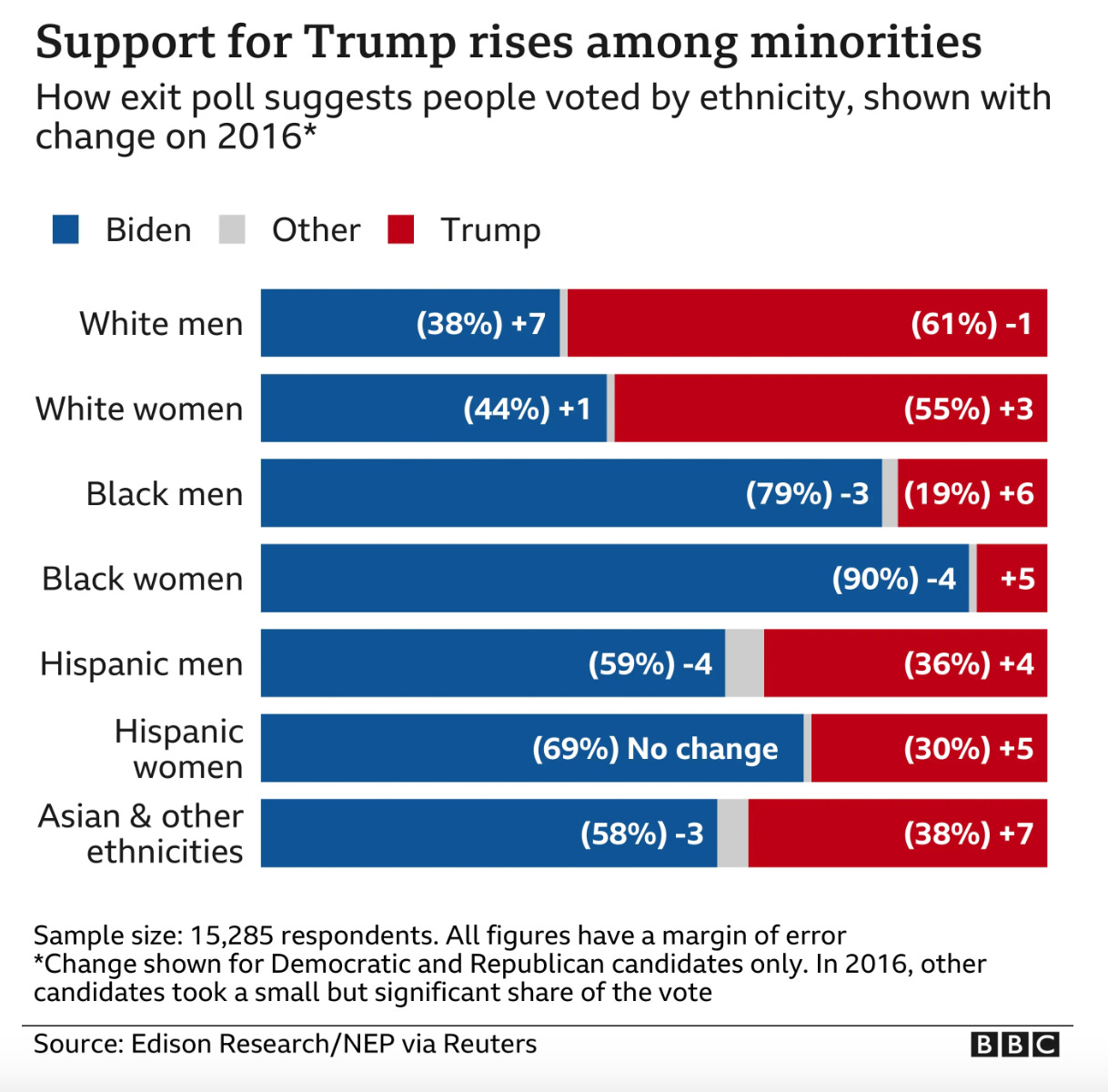

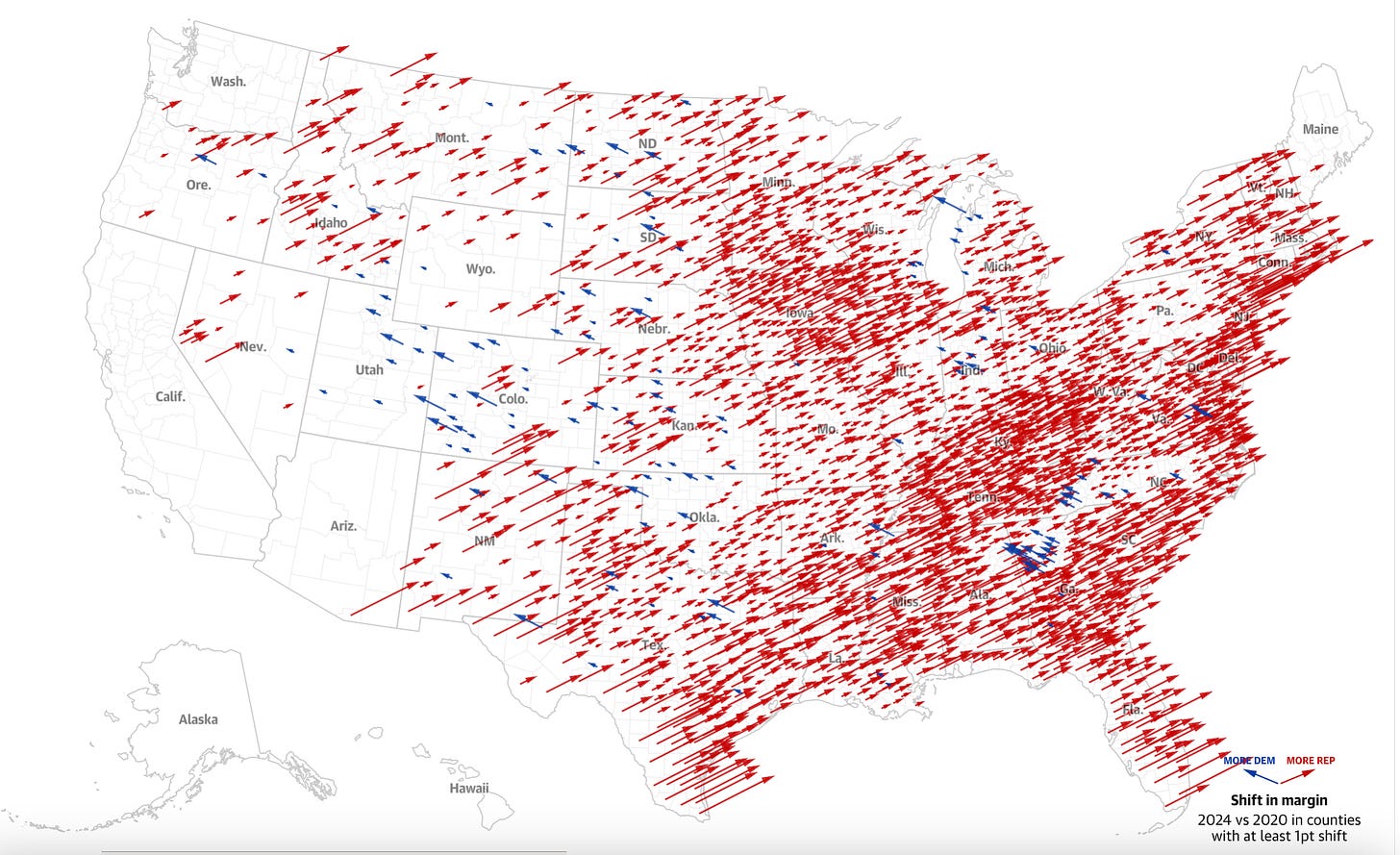

With the 2024 election now completed, everyone is doing an autopsy on what happened. In particular, Donald Trump won by a fairly large margin, but he did so by attracting a more multiracial electorate than in his previous elections (along with some students, discussed in my previous post).

Almost half of Latinos voted for the Republican Trump. In some of the most heavily Latino counties in the country, the swings toward Trump were unprecedented. He won counties that Republicans have not won in decades or more.

There were similar shifts toward Trump that happened with Muslim Americans in places like Dearborn, Michigan, or even in New York City within Asian-dominant districts.

On social media, I kept hearing jokes (or some comments made in earnest) about how these groups had become White or were trying to be White. Some of these comments were quite hateful, while others were more comedic.

Nonetheless, I could not help but think back to the old Chappelle’s Show The Racial Draft sketch. In the sketch, different races and ethnicities take turns drafting celebrities into their grouping.

Chappelle’s humor certainly leaned into the crass comedy that ruled the day then (an era dubbed the Vulgar Wave by LindyMan). He did always have a way of wrapping the comedy around social issues, though, especially when dealing with race.

In fact, I am writing this piece because the movement across races in the draft isn’t just a comedy sketch, our conceptions and understandings of race have indeed changed throughout history. The 2024 Election results are just another illustration of these shifts.

What is ‘Your’ Race?

One note on how I have been shaped on this topic comes from my time in graduate school at Columbia University. I had the chance to sign up for a class on census categorization with Kenneth Prewitt, the former US Census Bureau Director.

When I showed up on the first day, there were only a couple of students in the class. Dr. Prewitt told us he could not run the class with that low enrollment but he could do independent study with the three of us and we could just meet in his office. That worked for me.

So I showed up on Week 2 thinking that we would have a small group talking about his past work and his recent book What is ‘Your’ Race? The Census and Our Flawed Efforts to Classify Americans, but nope. I was the only student. No one else wanted to sit with the Bill Clinton-appointed, Senate-confirmed former Census director except for me.

For the rest of the semester each week for a couple of hours, he and I sat in his office doing deep dives into how racial categories were formed across history, how the categories worked with public policy, and the future of the categorizations. (That’s what grad school should be all about!).

A lot of the stuff that we talked about in 2014 proved prescient for 2024, which I draw on for this article.

White Melting Pot

The so-called father of our racial typologies is Carl Linnaeus, an 18th-century Swedish biologist, who established a global race system with four categories: Americanus, Asiaticus, Africanus, and Europeaeus. This 300-year-old system is still what our current US Census uses sans a Hispanic category.

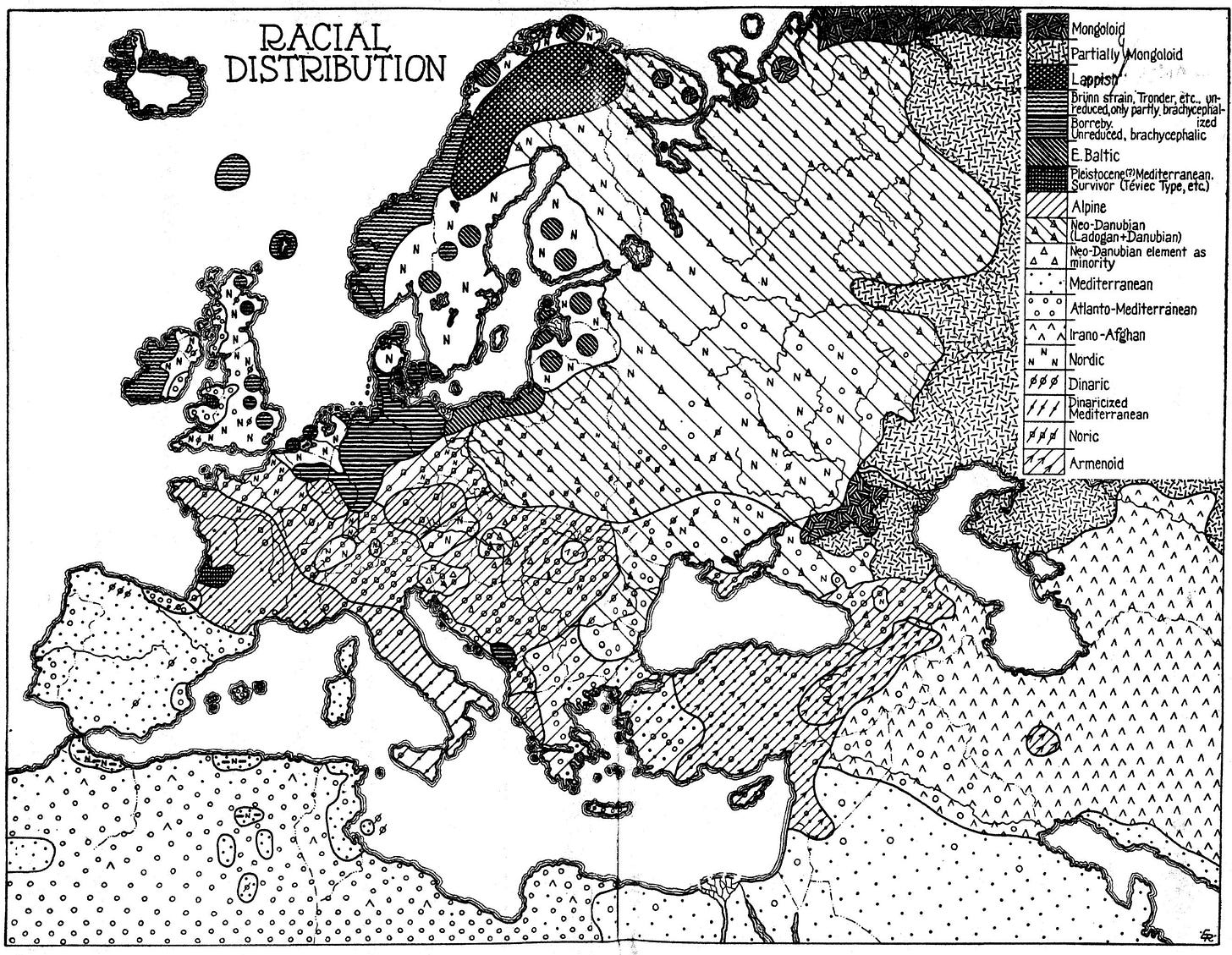

There were hundreds of other categorization systems. For instance, at one time, scholars broke up Europe into separate races such as Mediterranean, Alpine, and Nordic. Some of these early conceptions were used by Nazis to justify their ethno-nationalism or bunk science like Phrenology.

There was often a racist and ethno-nationalism hierarchy to these categorizations, including the one from Linnaeus that we still use. These hierarchies and conflicts manifested within Europe, often exacerbated along religious lines.

When these various European groups came to the US, they brought these sentiments of the Old World with them.

The distinction between White Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPs) vs. the other groups of mostly Catholic ethnicities from places like Southern Europe and Ireland was sharp. The WASPs ran the country, they were the elite, while everyone else was on the bottom.

You may recognize these conflicts from the film Gangs of New York, which dramatically portrayed the bloody battles between these groups in the Five Points neighborhood. Our old urban neighborhoods were heavily ethnic enclaves, such as Little Italy or Irishtown. The divides between these places and WASP strongholds were especially stark.

It would not be until after World War II that the US became the true Melting Pot that we often hear about. This intermingling happened with the suburbanization of our cities. People moved out of the old ethnic enclave slums and into the open spaces of the Levittowns.1

The old Euro identities rapidly eroded and the glob of broad White suburban American was crystallized. It did not happen overnight, and you can still see some of these tensions playing out in old post-War TV shows or movies.

America’s Real Racial Draft

One example of how these conceptions change is from Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz of the classic sitcom I Love Lucy (among others) from the 1950s. Arnaz was Cuban and Ball was White. Today, we might look back and think this was a kind of interracial couple. But it wasn’t, not in the way we think about that definition today.

Instead, it was an intra-White couple. Their relationship poked fun at the same ethnic strife discussed above.

It would not be until 1980 that the US Census inserted the Hispanic ethnicity question.2 Once added and behind a wave of social movements, the racial categorization became more crystalized in the minds of Americans. This even included White Cubans like Arnaz into this category (though not without controversy).

Just recently, after decades of negotiations, the Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) category was added to the US Census in 2024. This MENA grouping, who were formerly just categorized as ‘White’, can include heritages from Egyptian and Jordanian, to Israeli and Palestinian.

You can probably already tell that this MENA bloc is going to have widely different political and social sentiments—just like what played out in the recent election.

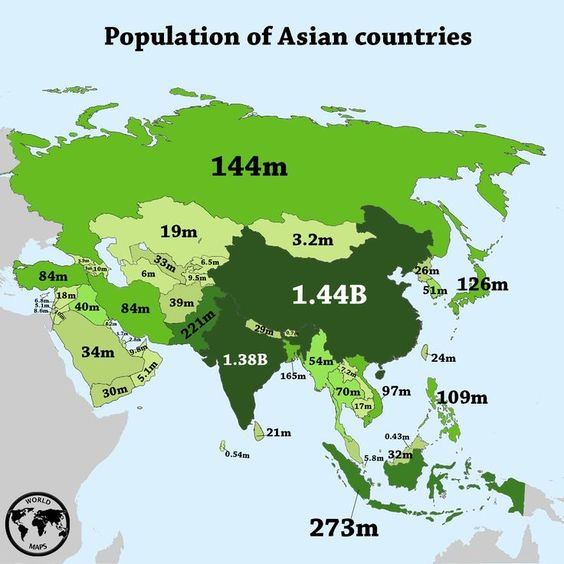

The Asian American categorization was similarly thrown together by the Census through rounds of discussions. Never mind that Japanese Americans and Sikhs may have widely different experiences and even phenotypes, they became one single category molded to the 18th century Linnaeus classification.

More recently, there has been the creation of Asian American and Pacific Islanders (AAPI). The US government even has a distinction of universities serving Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander with the alphabet soup acronym AANAPISI.

These groupings do not even include the BIPOC grouping, which is not on the Census, but which has been popular on university campuses and more liberal-leaning groups.

2024 and Beyond

The 2024 election showed that these groups are not simply voting as a unified bloc—not as the mass BIPOC grouping nor even within each racial categorizations. There are considerable variations within each group that change across time.

It is not simply that Latinos have been drafted into the White category like Italians apparently were in the post-war suburban experiment, to continue the Chapelle’s Show metaphor. Instead, it is that our categories always had movement around them and friction within them.

These groupings simply cram so many disparate peoples together when they are not giant monolith voting blocs. It shouldn’t be a surprise when sociopolitical changes happen in different directions within these broad groups, like a good portion of Latinos moving right in the recent election.3

Democrats, then, seemingly overestimated snapshots without fully considering the possible shifts. Yes, demographics are destiny, but that destiny isn’t static.

In Dr. Prewitt’s What is ‘Your’ Race?, he advocates that we move away from these Linnaeus categorizations that are based on an 18th-century view of the world. Instead, he argues that we should attempt to categorize through national origins the best we can.

In his system, for instance, there wouldn’t be a focus on AAPI because Korean-Americans would be broken up from Nepalese-Americans. For Black Americans, there would be a separation of American Descendants of Slavery (ADOS) from recent generations from the Caribbean or African countries.

Of course, with a more mixed-race society, these national origin points become more fraught. Nonetheless, Prewitt argued that it would better allow us to move beyond some of the frictions and misrepresentations caused by the current classifications.

I do not see this complete reclassification happening anytime soon, but there are now more people questioning our adherence to rigid boxes due to the surprising 2024 election.

Trump shook the electorate by drafting new racial and ethnic groups to his base in unexpected ways. The results may provide an opportunity to rethink the focus we place on these limited categories in the future.

Note that Black Americans were often left out of these post-war suburban developments due to both de jure and de facto discrimination.

Technically, the ethnicity categories in the US Census is a sub-category under the other races. So a respondent should mark Hispanic and White, or Hispanic and Black, rather than just Hispanic. Functionally, though, in the way that it is reported in media and academia, Hispanic is treated as a comparable category to the other races.

Looking at broader Latino reaction to the Latinx label is worthy of a future post.