Rise of RedNote Shows Americans Need to Study Abroad in China

US Students have stopped studying abroad in China but the migration to the TikTok replacement proves there is appetite for bolstering people-to-people exchanges.

The banning of TikTok in the US sent users panicking, many of whom were Gen Z, to find alternatives to the video-sharing app. One of the replacements came in the form of another Chinese app with similar functionality called RedNote (小红书, Xiǎohóngshū, or literally Little Red Book).

One key difference between TikTok and RedNote is that the latter app allows users from China and the US to interact, at least for now. The Chinese version of TikTok is called Douyin - or the American version of Douyin is TikTok - and the user bases are separate for each app.

This separation is not the case for RedNote, meaning that Americans were engaging with Chinese content for the first time, and vice versa, with the TikTok ban. The mix created some memorable moments of cultural exchange. A content creator put together a montage of some humorous interactions and memes from this digital exchange.

These interactions show that when there is a people-to-people exchange, people usually find common ground and humanity in each other—even if supposed adversaries. It also highlighted how little many Americans knew about China. The Zoomer TikTok refugees were amazed by the skylines, electric cars, groceries, and just life in general.

The reactions to these digital exchanges showed me how much Americans are starved for interactions with China. Few Americans study in China, Mandarin language classes have cratered, and misconceptions or stereotypes run rampant. It’s time to turn these trends around—even if it’s not easy.

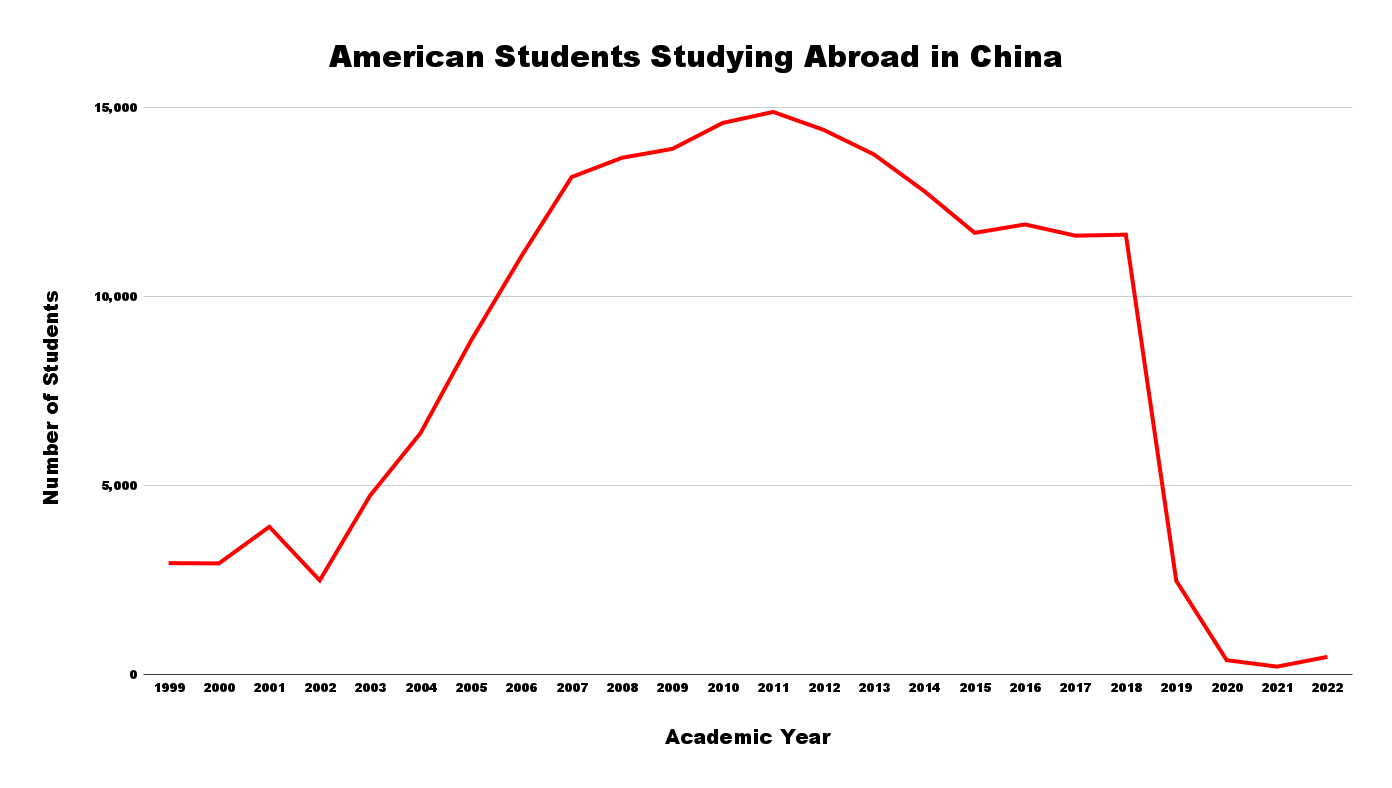

Studying Abroad in China Cratering

One reason for the rampant misinformation and misunderstanding of China is that Americans no longer study abroad in the country. Since the COVID crisis, there have been fewer than a few hundred American students studying in China during an academic year, according to Open Door data from the Institute of International Education.

Granted, the pandemic was taken much more seriously in China than in other countries, and it was almost impossible to travel to the country for a couple of years. I returned right after the travel restrictions had been mostly lifted in the summer of 2023. There were very few if any Americans at the universities I visited. It was a jarring juxtaposition from when I studied abroad at Beijing Normal University in 2017 when Americans were a common sight on campuses.

Upon my return, there were material blockages in getting to China, such as massively inflated travel costs, along with the aftermath of COVID. But the number of students has barely risen even as we get a few years out from the pandemic. This indicates that it wasn’t just the pandemic hindering China as a study abroad destination.

There was a peak of American students studying abroad in China during the early 2010s, especially with the push from the Obama administration’s 100,000 Strong initiative. The program was spearheaded by Hillary Clinton and targeted a massive boost of Americans studying in China. “Today, I offer this challenge to leaders of American institutes of higher education and study-abroad providers: Double the number of your students who study in China by 2014.,” wrote Clinton.

While there was an initial boost around this time, the outflow numbers fizzled as the decade proceeded. In a metaphor for how the mission went, the website for the initiative was abandoned and now the URLs are an Indonesian celebrity gossip blog and a Chinese gambling site.

Conversely, Chinese students have still been coming to the US in large numbers, even if there has been slower growth and drops due to strained relations. IIE reports 277,398 in the 2023 academic year. RedNote is showing a new generation of Americans what they might be missing.

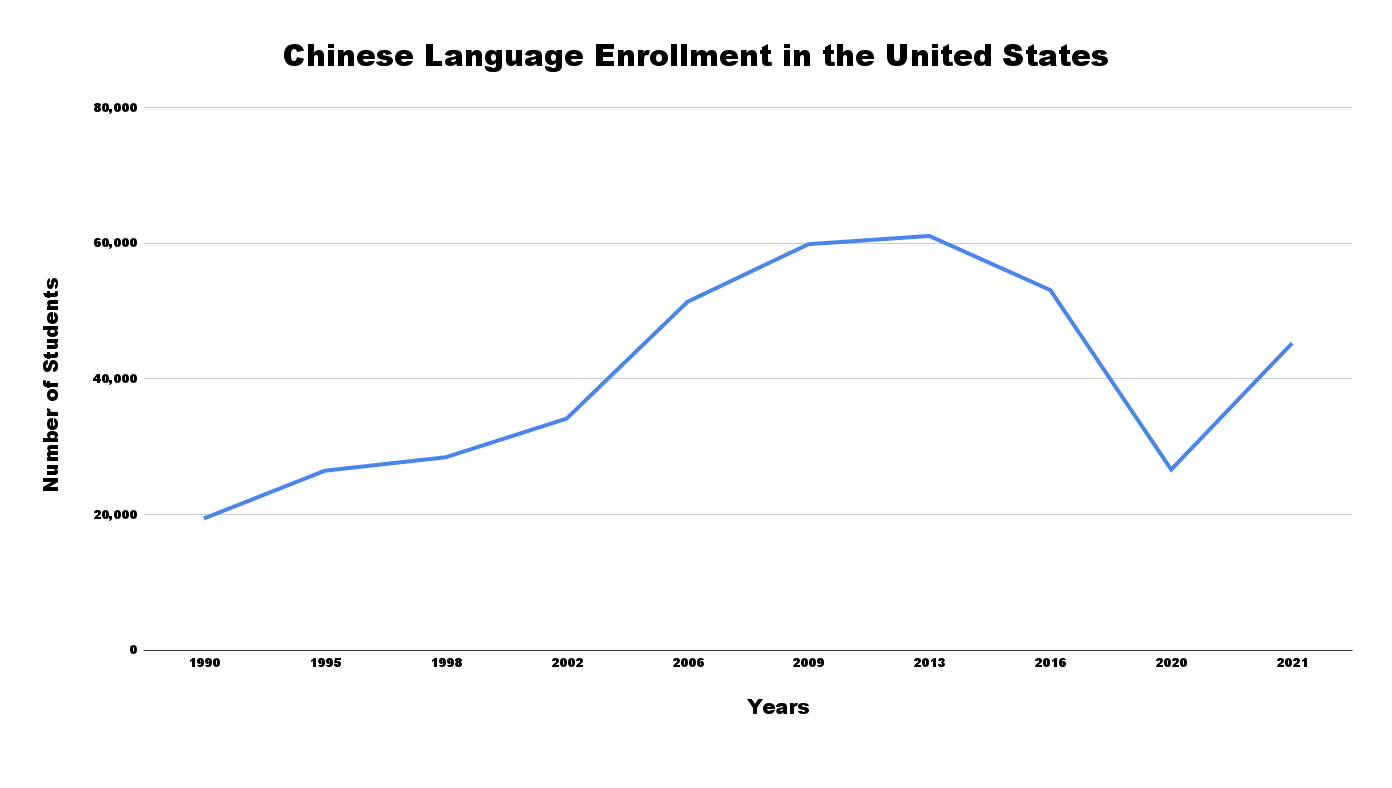

Chinese Language Learning

What I am hoping comes out of the growing interest is a rediscovery of real Chinese classes through schools. Unfortunately, the language has waned in popularity in recent years. Looking at data from the Modern Language Association (MLA), there was a steady rise in American student enrollment studying Chinese language from the 1990s until around the early 2010s. There was then a large drop even before COVID.

One of the outcomes of the migration to RedNote was that Americans started to learn Mandarin. The RedNote interface was only available in Chinese characters early in the mass adoption, forcing users to learn a bit of Hanzi. This propelled people to start using Duolingo. The language learning app reported a 200% increase in users compared to the same time last year.

While I am glad that people are getting into the language, I actually don’t think the app is very good at teaching Mandarin. As someone who has taken years of classes in the language, including on Duolingo, there is a need for real tutors early on in the process (e.g. getting the tones right). Duolingo simply cannot offer this kind of personal learning.

One problem is that Chinese Institutes became targets in the diplomatic spat between the two countries. Throughout the US these Chinese-funded language and culture centers have been getting shut down, leaving some places without other classroom options.

Confession time: I took classes through the Chinese Institutes and received funding from the headquarters to do research in China. So perhaps you aren’t going to trust me when I tell you that these programs were mostly just language. The research funding was even hilariously hands-off. They gave me a bunch of money and I just traveled around China without much oversight. This was in 2017, so things have certainly changed in broader China studies circles, but this has been more my experience with the Chinese Institute programs in general.

Nonetheless, even without taking money from the Chinese government or allowing more Confucius Institutes, we need more youngsters learning Chinese. If that happens via Duolingo, so be it, but I think our universities would be much better equipped to train future generations in this space. Funding, though, has been an issue for the languages in higher education. So part of this is convincing young people this is a worthy endeavor.

Old Ways of Viewing China

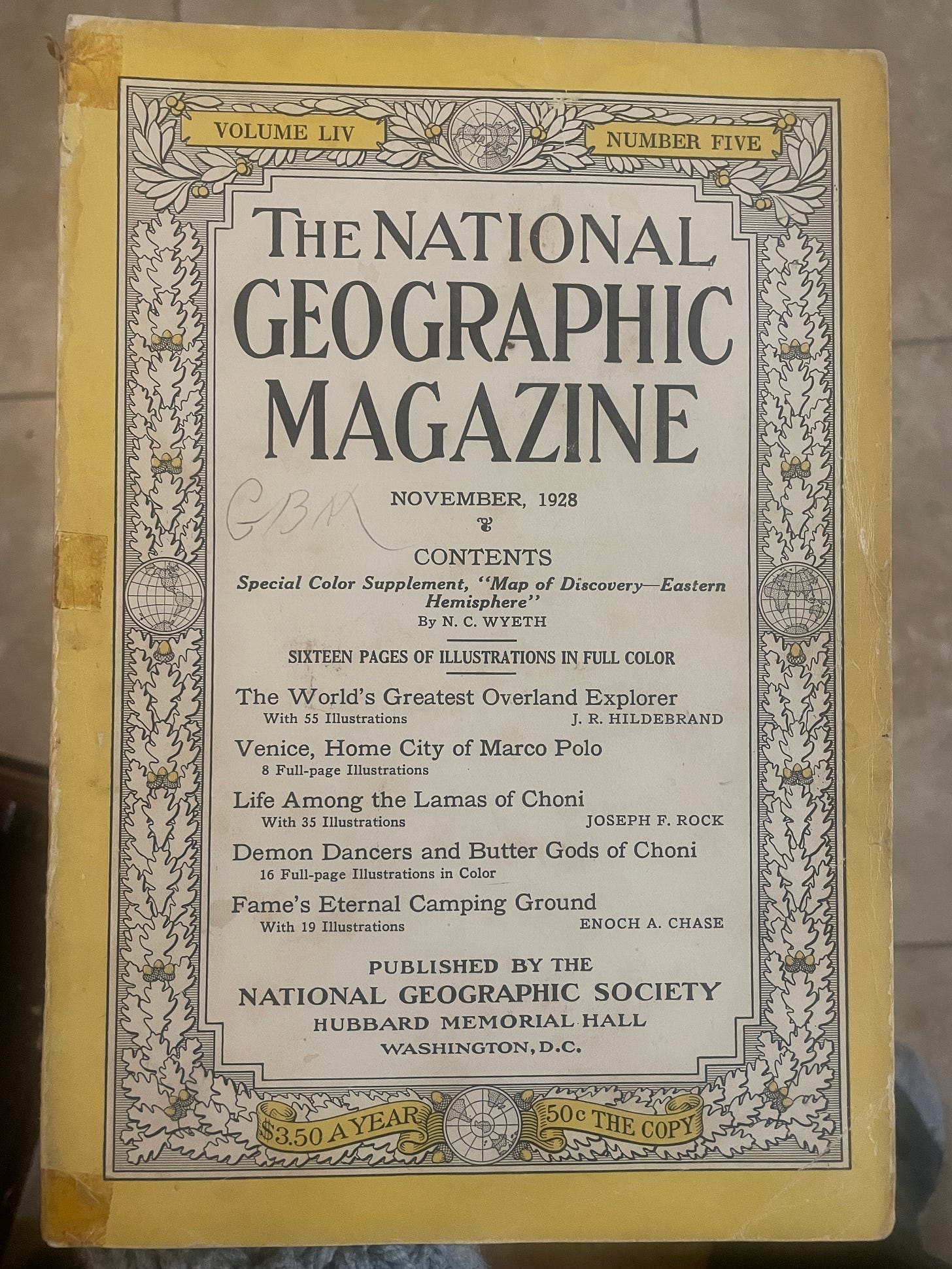

Another reason for RedNote users’ excitement in seeing life in China is that depictions of the country in the US still often harken to flat stereotypes. These remnants of perceptions from a century ago, when it was still largely locked away to the public, merely the mystical Far East “Orient.” I see these types of descriptions in my old issues of National Geographics. In one issue from 1928, a team of adventurers described their journey:

There, in to-day's "Wild West" of China, where a National Geographic Society expedition braved bandits to bring back blight-resisting chestnut trees and new rhododendrons and much scientific data, Marco moved serenely on his observant way.

While it may have made sense for visitors in the 1920s to view China as a mystery, travel was generally more difficult then and especially so in China. Not to mention the turbulent era in the region during this period.

It also may have made sense when China was largely closed off to the US for 30 years from 1949 to the 1970s before normalizing relations. Indeed, there was a boom of interest in the country after Nixon’s visit and later with the normalization of relations between the two countries.

But Americans shouldn’t still view China with the same kind of mystery as early twentieth-century adventures nor when our hippy ping-pong team went over there in 1971. More cultural entry points will help shape these perceptions, such as playing the popular Black Myth: Wukong video game or other interactions on RedNote. But the real change comes from seeing and studying a place with your own eyes and feet.

China Beyond the Filters

I am under no illusions that China is a perfect country, far from it. Users on social media famously boast curated images to paint a more positive, affluent, and exciting lifestyle—no matter Instagram, TikTok, or RedNote. This includes myself, with posts like the one below of awe-inspiring Chongqing (along with the massive crowd I didn’t initially include).

A lot of Americans on RedNote are getting an insight into the upper crust of Chinese society. The GDP per capita between the countries is still wildly divergent (≈ $64,000 vs. $18,000). There are still vast poor regions throughout China, and the government insists on keeping the “developing” label.

So when American RedNote users are shocked about China’s cheap groceries, 40-hour work weeks with good vacations, and advanced technology, these things need contextualization within the overall affluence of the society. This is why actually going to the country and living there offers a truer experience that cannot be filtered over with an AI gloss.

Students going to study abroad in China will find things they love, things they hate, things that surprise, and things as expected. Being there is a much fuller experience than old tropes in traditional media or sleek posts on social media.

Barriers to Studying in China

Admittedly, there are still issues with going to China as an American. The biggest concern prospective students may have is regarding security or political fighting. While these issues may deter some, yes, the outflow numbers were wildly outbalanced even before recent diplomatic relations and incidents.

For me, there are bigger issues in the form of annoyances. When I was there in 2023 much of the banking sector was still closed off to foreigners. Most stores have gone cashless, instead using apps for buying things—clothes, beers, coffee, meatballs (I stopped in the Shanghai IKEA). At the time, I was with a group of foreigners who could speak good Chinese and all lived in the country in the past and found the new system burdensome.

However, I have been told that the banking issues have been cleaned up for foreigners since I have been gone, so things should be easier now. Further, universities and schools that I know have done a pretty good job of getting their international students right when they arrive. There will always be some barriers though.

Another issue I find annoying is the Great Firewall. I could probably use a good social media cleanse from time to time. But the limitations on Western sites is frustrating, especially if something is needed for work. Buying a VPN is a necessity, and even their efficacy is spotty much of the time.

There are rumors that there may be some movement in this space. Shanghai could open its Internet to more Western sites such as Facebook and Google as a kind of pilot test. While this doesn’t mean the floodgates are opening, it should make studying at Shanghai universities much more manageable. Oh, how I missed Google Scholar when I am there!

Of course, studying abroad is expensive and not everyone can do it. While there are scholarships, I wish the US government expanded more opportunities for students to go to China. If the costs are insurmountable though, there are other opportunities such as teaching abroad.

We Need Americans to Study Abroad in China

Even despite the issues, I think studying in China is worth it. For me, I am more thinking in terms of peace and understanding through human-to-human interaction. I believe in the cultural diplomacy approach, which can be critiqued as a so-called China Dove.

But even for those who are more hawkish on China, viewing them not as a rival but as a true adversary, there should be a recognition that expertise on the country is crucial. Chinese students come to the US, they learn English and our culture, they understand the country. If you are a China Hawk, wouldn’t you want some Americans to have that same expertise of the target adversary?

With fewer people studying Mandarin and cratering study abroad, the US is losing out on this comparative advantage.

, Associate Professor at Princeton University, made this same case in a Washington Post piece last year, “The United States is running critically low on China expertise.”Either way, for China Doves, more engagement and cultural exchanges are needed for peaceful understanding; and for China Hawks, more language learning and cultural insights are needed for intelligence gathering. Both views mean more Americans need to study abroad in China. The TikTok refugees on RedNote prove that young Americans are not only up for it, they are craving this experience abroad.